Continuing my series of articles detailing the history and production of Turn A Gundam! My goal is to provide an accessible source of context and knowledge for reference purposes, and to improve community discourse. This is the culmination of research I’ve done and continue to do over the past decade. It’ll be divided into four parts for easy reading as follows. I highly recommend you read and familiarize yourself with previous parts, as there is a lot of overlap between them.

- Part I – Victory Gundam & Battling Depression

- Part II – Influences & Inspiration

- Part III – Prelude to Turn A Gundam

- Early beginnings

- Brain Powerd

- “Ring of Gundam”, The “A Gundam Project”, and Tomino Memos

- Akira Yasuda, Syd Mead, and Yoko Kanno

- Goals and Aspirations

- Part IV – The Era of Turn A Gundam

Without further ado…

Planning for a “New Gundam” began on April 10, 1997 when Yoshiyuki Tomino was approached by then-Sunrise CEO Takayuki Yoshii. He immediately requested Hiroyuki Hoshiyama as a scriptwriter for the project, which Sunrise happily obliged. Hoshiyama was an industry veteran who had previously collaborated with Tomino on Daitarn 3 and the original Mobile Suit Gundam. Tomino specifically sought him because he was not tainted by modern Gundam ideas and brought a fresh perspective from his experience outside of mecha anime. The two went back-and-forth and brainstormed ideas and philosophies. Hoshiyama suggested “Gundam, but in a world like Heidi“, with an abstract idea of a “nice guy” protagonist who “smells good”—Hoshiyama often emphasized smell in his works—walking through a wheat field while a mobile suit flies above. Heidi, Girl of the Alps (1974) was a pre-Ghibli anime directed by Isao Takahata noted for its idyllic atmosphere and picturesque art style and backgrounds, invoking a sense of tranquility; iyashikei, essentially. Tomino was involved in Heidi as a storyboard artist, and it proved to be an important work in his budding career at the time. He gained a lot of respect for Takahata and Miyazaki, and in the 90s viewed the pair as the leading directors in the anime industry. He wanted to channel some of their methods of success into his own work, particularly when it came to assembling a team with different stylistic approaches. In Turn A Gundam Tomino wanted to emphasize a grounded view of conflict with an atmospheric healing effect, to convey a sensation of acceptance and happiness.

By June of 1997, Tomino was drafting character designs with his new friend Akira Yasuda. At this stage of planning, the notion was to “affirm” all older Gundam titles and only names and basic roles of characters were discussed. Shortly afterwards, Sunrise Studio 1 re-shifted its focus to Brain Powerd and the new Gundam project was temporarily filed away.

TURN A GUNDAM PRODUCTION CHRONOLOGY

1997, April — Yoshiyuki Tomino is approached by then-Sunrise CEO Takayuki Yoshii and planning begins for a new TV Gundam project.

1997, June — Akira “Akiman” Yasuda’s involvement in the project is decided and the earliest-known character concept sketches are drawn.

1998, Spring — The document for a proposed “Ring of Gundam” is put together, with a planned Fall 1998 broadcast date.

1998, April — Broadcast of Brain Powerd begins.

1998, June — Syd Mead is approached and offered the job of lead mechanical designer.

1998, July — Syd Mead visits Japan and meets with Sunrise executives.

1998, August — As part of the “Gundam Big Bang Project”, the “Gundam A Project” is announced as the newest TV series. At the event, Yoshiyuki Tomino, Akira Yasuda, and Syd Mead make appearances.

1998, September — The main story outline is formalized and scenario work for individual episodes begins. At the meeting for the first episode, Loran’s origin is changed from Earthling to Moonrace.

1998, October — Akiman moves to Sunrise Studio 1 and starts full-scale character and setting work. He ends up working at Sunrise for about half a year.

1998, November — Broadcast of Brain Powerd finishes.

1998, December — Animation work for Turn A Gundam begins.

1999, February — A press conference officially reveals Turn A Gundam to the world. The design of the titular Gundam is publicly unveiled and debate over its mustache becomes a trending topic.

1999, March~April — Syd Mead is tasked to design the Bandit and Turn X as later portions of the plot are discussed.

1999, April — Broadcast of Turn A Gundam begins.

1999, May — The second half of the story is polished as ideas go back-and-forth.

2000, April — Broadcast of Turn A Gundam finishes.

BRAIN POWERD

It’s important to discuss Brain Powerd (1998) to establish some context, as the two anime’s existences are intertwined. This is not a summary nor breakdown of its own production history, but rather a brief examination of how it relates to Turn A Gundam. As previously mentioned, during his years of depression Tomino looked inward to the women in his life and sought to promote a “feminine” touch in Turn A Gundam, involving more women on staff than the norm. This mindset was prevalent to a degree in Brain Powerd as well, and as a result both shows allow its female characters to take centerstage. The character Hime is often said to be made in the spirit of Tomino’s wife (hence, the endearing name “hime”), and the three kids are named after their two daughters and the family dog—Akari, Yukio, and Kumazo. The two shows also have several carryover staff members; notably in scenario writing (Miya Asakawa and Tetsuko Takahashi) and voice acting (Akino Murata, Kumiko Watanabe, Romi Park, and Gou Aoba), along with many other staff. Romi Park’s first major anime voice role was Kanan Gimms from Brain Powerd, and she views it as a memorable role that allowed her to meet new people and kickstart her career. Romi Park and Akino Murata would go on to voice Loran Cehack and Sochie Heim, respectively.

Tomino was still battling depression throughout the entirety of Brain Powerd, a fact he himself has acknowledged. You can see it in the way the show examines his state of mind; it presents a lot of moving commentary and self-examination that culminates with emotional catharsis. Naohiro Ogata (currently a producer at Sunrise) has remarked that Tomino was still in “angry mode”—reminiscent of his 80s self—during Brain Powerd‘s production, and it wasn’t until Turn A Gundam and King Gainer that he calmed down. There was sentiment among staff members that everything he worked on “becomes Gundam”—in the sense that unique ideas inevitably revert to an in-studio Gundam standard—and Brain Powerd supposedly suffered the same fate, the “curse of Gundam” striking yet again. The show also had only one sponsor and didn’t receive particularly good TV ratings. But while Tomino and his staff struggled during its production, they found it a necessary stepping stone to pave the way forward. Tomino hadn’t directed a TV anime since Victory Gundam, so he knew he had to make something before Turn A Gundam or he felt he’d never be able to make anything Gundam-related again. Thus, he found himself feeling desperate during Brain Powerd, and much of the show’s unevenness can be attributed to that. Turn A Gundam‘s planning and pre-production was happening as Brain Powerd aired, and setting documents for the new project began to circulate around in the studio, causing negativity from staff members, i.e. “it’s Gundam again…” Tomino tried his best to drown out the negativity and was determined to restore the franchise’s honor from within. He did not see a bright future for Sunrise otherwise.

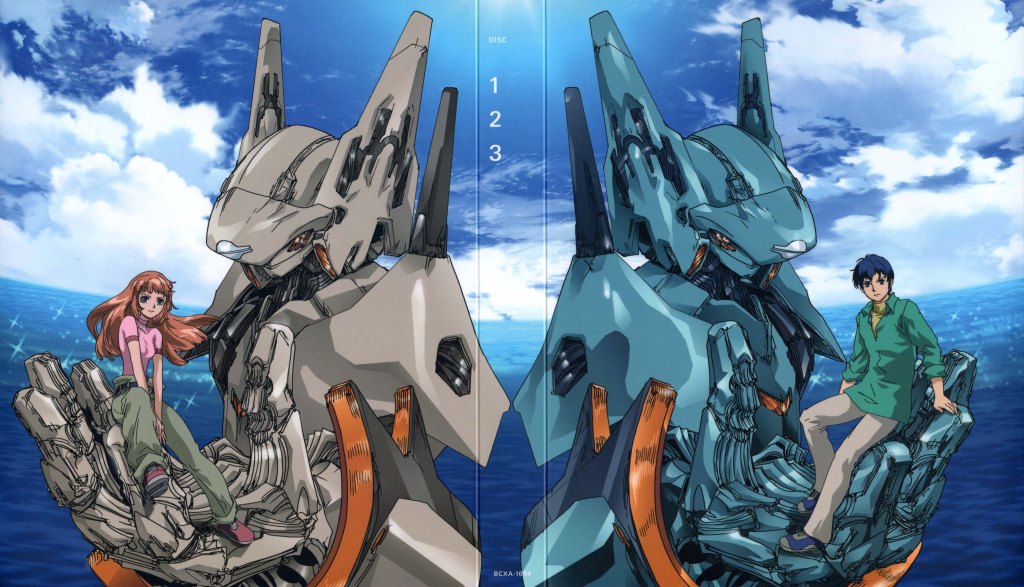

That said, while not a particularly popular entry in Tomino’s filmography, Brain Powerd‘s influence can still be felt today, as Gundam Reconguista in G (2014) borrows elements from both Brain Powerd and Turn A Gundam. It recently received a magnificent Blu-ray release in March of 2022.

“RING OF GUNDAM” and the “GUNDAM A PROJECT”

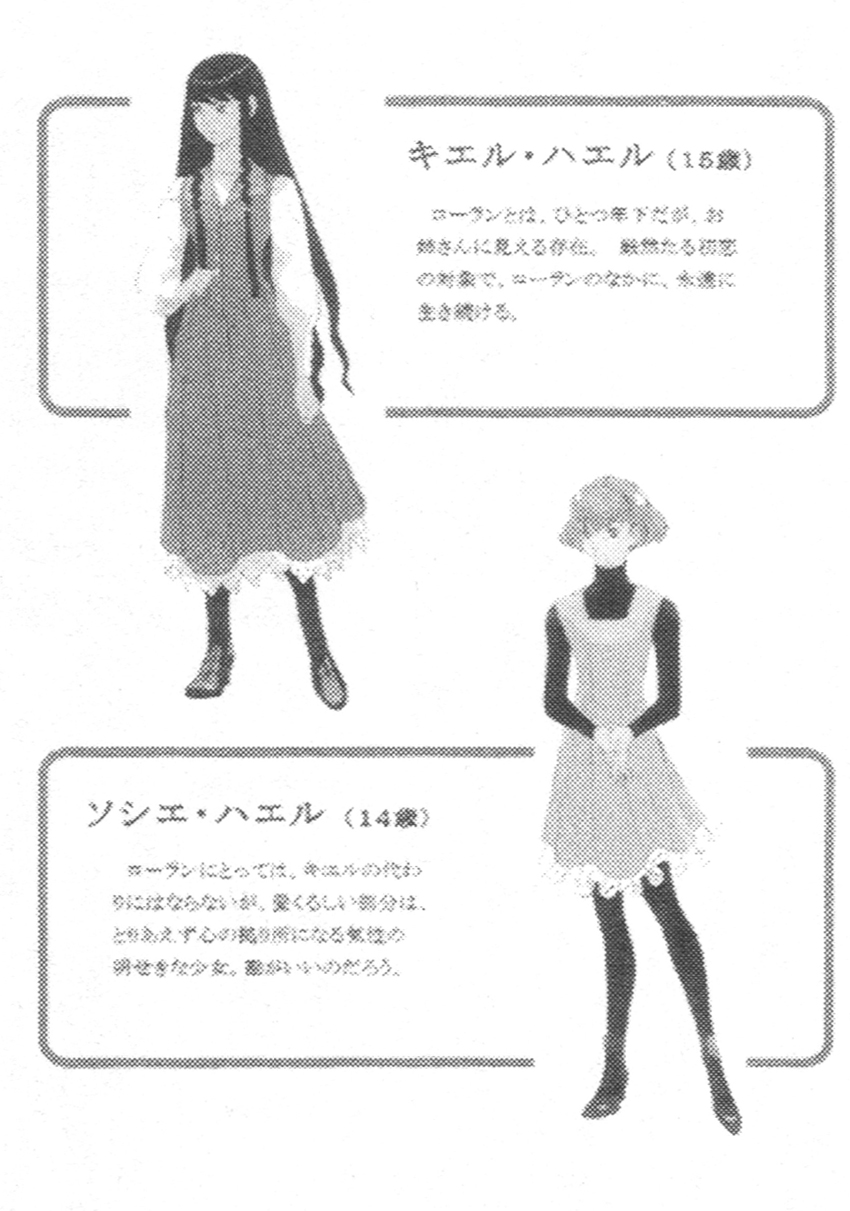

The original internal working title of Turn A Gundam was “Ring of Gundam”, and a planning document was published early in the spring of 1998 with many details. Tomino wanted to deliver a story that would expose the origin of humanity’s sin, and in doing so he aimed for a “restoration” of Gundam from mecha otaku to appeal to a wider audience. This idea stems from a canned Ideon project called “Ring of Ideon”, which too focused on a theme of restoration. In “Ring of Gundam” the concept of encompassing “all”, i.e. the ∀ mathematical symbol was not yet clearly defined, but “going in circles” was a running theme. Thus, “Ring” of Gundam. The setting and time period were also unclear—aside from an overarching Earthling vs. Moonrace conflict—but humanity being unaware of the concept of war was a prevalent plot point. An Earthling named Loran Sohack is in love with Kihel Hael, who dies early on into the story; hence the name “Kieru” (note the surnames “Sohack” and “Hael”). Her death is what spurs Loran and Sochie to join the Militia and combat the Moonrace invaders. Dianna herself isn’t confronted until Loran & co. reach the Moon and learn of humanity’s “original sin”. The concept of a masked rival character exists but isn’t fleshed out, and minor characters like Poe and Miashei are mentioned. The Moonrace’s sphere of influence also extends beyond the Moon into nearby space colonies. The “Ring of Gundam” name might sound familiar to Gundam fans, since Tomino did repurpose the title many years later for a five-minute short video to celebrate the franchise’s 30th anniversary. There is no meaningful connection between the two, aside from very surface level themes.

The “Gundam Big Bang Declaration” was an event that took place on August 1, 1998 at the Pacifico Yokohama Convention Center. A celebration of Gundam‘s 20th anniversary, it kicked off the “Gundam Big Bang Project”. The sold-out venue was packed with fans, booths, and even 1/9 scale replicas of the RX-78-2 and Zaku II. The event was hosted by Kazuki Yao (Judau Ashta), Kumiko Watanabe (Katejina Loos), and Shuichi Ikeda (Char Aznable) and featured guest appearances by Nobuo Tobita (Kamille Bidan), Saeko Shimazu (Four Murasame), Tomokazu Seki (Domon Kasshu), Yōsuke Akimoto (Master Asia), and Haruhiko Mikimoto, among others. The “Gundam Big Bang Project” consisted of the following:

- Gundam: Mission To The Rise, a three-minute CGI short film that aired at the venue.

- New special edition releases of the Mobile Suit Gundam movie trilogy.

- The release of The 08th MS Team – Miller’s Report and Gundam Wing Endless Waltz Special Edition in theaters.

- The announcement of G-Saviour, a live action + CGI film set in the Universal Century timeline.

- The announcement of a new TV Gundam tentatively titled “Gundam A Project”. It’d mark the return of franchise creator Yoshiyuki Tomino, who made an on-stage appearance with fireworks and applause. Akira Yasuda and Syd Mead also made appearances as character and mechanical designers, respectively. Tomino declared that his new project would “affirm” all the events of the Gundam series so far, including G Gundam. He also promised that the show would have a lot of great female characters.

As the summer of 1998 continued, basic plot structure and character roles slowly began to come together and vaguely resemble the final version. Turn A Gundam‘s scenario underwent many changes in the year leading up to its broadcast, and even while it was airing changes were continually being made to later parts of the story. This is what’s known as Tomino’s “live-action approach to storytelling”, where details are decided as the plot moves along. During scenario meetings, Tomino would hand out preliminary plot guidelines covering X number of episodes for the scriptwriters to work with. Dubbed “Tomino memos”, these broad storylines would then be selectively refined to form the plot and scenario as we know it. This is modus operandi for Tomino—the term “Tomino Memo” is nothing unique to Turn A Gundam. The “Gundam A Project” codename remained well into 1999, just months before the show was scheduled to air, and by its latest project proposals most of the outline and setting information resembled the final version.

I’ll briefly cover some of the main character scenarios to paint a picture of how ideas evolved via drafts and memos, as it provides insight on subtler aspects of character roles and personalities. Some of the cut ideas actually resurface in supplementary non-canon material (manga, novelizations, etc.).

- Loran Cehack—an Earthling in much of the earlier drafts—is a humble and handsome young man sometimes mistaken for a girl (“Laura”) who addresses himself using the “boku” (僕) first-person pronoun. An engineer-in-training, he ends up having to work in the mines. He’s characterized as a “nice guy” and has sharp reflexes that can be applied to mobile suit combat (it’s noted that he is NOT a Newtype). In nearly every revision—including the final version—Loran is smitten by Kihel Heim to some degree. This is intentional, because Tomino wanted Loran to be infatuated with a blonde woman, and that love is later redirected to Dianna Soreil. His devotion to Dianna remains unparalleled even in drafts where she takes on a more antagonistic role. When Loran’s origin is changed from Earthling to Moonrace, the infatuation instead stems from Dianna herself.

- Dianna Soreil is the Soreil family matriarch and leader of the Moonrace. She yearns for the blue skies and greenery of the Earth and passionately feels the suffering of all people on both sides of the conflict. Her connection to Princess Kaguya from The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter is more explicit in earlier drafts & memos, with Dianna’s dream of “becoming Kaguya” specifically mentioned and Loran allowing her to “fulfill her destiny” being a running theme. Her romance with Loran is also more pronounced, something that is much subtler in the TV broadcast. In some revisions she even pilots a mobile suit called the Moonlight Butterfly.

- Kihel Heim‘s a little complicated, because originally she was simply meant to be a one-off character who dies early on. By later drafts, she’s an ambitious young woman aiming to marry up the social ladder (Guin Lineford’s name is naturally considered) who doesn’t hesitate to weaponize her social standing. The fact that she’s the spitting image of Dianna Soreil forces her to face challenges and embark on a soul-searching journey. She dislikes it if/when people mistake Loran for a girl.

- Sochie Heim‘s probably the character who saw the least amount of changes on a surface level. The younger daughter of the Heim family, she dislikes the way her sister lives her life and chooses to be a free spirit. When the Dianna Counter invade, she decides to fight them in order to protect her family. It’s noted that she’s meant to break the stereotype of the “childhood friend”, because it is necessary for the men of the world to know that no such convenient girl exists. In earlier drafts, she doesn’t have a crush on Loran and her potential romantic partners are up in the air.

- Guin Lineford is described as a young Kakuei Tanaka, the Prime Minister of Japan from 1972 to 1974. Tanaka had strong ties to the aerospace and construction industries and was involved in many political scandals, eventually having to retire in shame. His sense as a businessman is modeled after Howard Hughes, a 20th century American business magnate. Guin’s homosexuality is more pronounced in earlier drafts. While he knows how to have have “fun” with girls for social benefit, he pushes away anyone seeking a meaningful connection, including Kihel. It’s suggested that he was sexually abused in his childhood and as a result fixates on Loran to an unhealthy degree. He also takes on a bit of a more active role and even pilots some fighter aircrafts.

- Harry Ord was initially billed as a standard antagonistic masked rival character, but he saw many changes as the plot evolved. Captain of the Royal Guard, he lives his life with the conviction of protecting Dianna at all costs. He pilots a mobile suit called the Amanma, named after his ex-wife of the same name who herself appears as a character in the story. His romantic partner constantly changed, cycling between Miashei, Poe, Sochie, and finally settling with Kihel.

- Phil Ackman is a mid-level officer in the Dianna Counter who’s frustrated with Dianna’s soft ways, and Poe Aijee has hostile feelings towards Loran for betraying the Moonrace.

On February 16th, 1999, a press conference was held in Tokyo to reveal the new official title as Turn A Gundam. The conference was attended by Tomino and other Sunrise staff and industry people, and there was lots of buzz and excitement. At the conference, images of the titular Gundam were revealed for the first time and Tomino addressed the following:

- To respond to mixed opinions about Syd Mead’s mechanical designs, Tomino claimed that his designs are symbolic of an industrialized society, and that it is only natural as humans to have a instinctive resistance to accepting such change. He claimed that Akira Yasuda’s character designs would balance out the clash in aesthetic.

- Turn A Gundam wouldn’t focus on typical Gundam-like topics such as Newtypes and space colonies because he doesn’t want them to be used as a hook for standard otaku.

- He doesn’t like the concept of the “end of the century”, because it drives oneself to a dead end. Humans are capable of accepting the coming-and-going of cycles, and he wanted to use Turn A Gundam to teach that lesson to both adults and children alike.

- He wanted to tackle the questions of the upcoming century: economic challenges, scientific developments, improvements in daily life, and the growing threats of climate change and environmental concerns. He didn’t believe one can get anywhere with a worldview that only moves in a “straight line”. He’s making Turn A Gundam because nothing would come of a project that simply just “extends the line”. He wanted creation to be a challenge. He admitted that it took him too long to finally realize all this, but he’s ready to face his embarrassment and start anew with Turn A Gundam. He is returning to Gundam with a brand new outlook.

Turn A Gundam was set to begin airing on April 9th, 1999 and was promoted on TV and in magazines. It marked the return of franchise creator Yoshiyuki Tomino, his first Gundam series since Victory Gundam in 1993, and would be the first Gundam to broadcast on Fuji TV. As the synopsis was revealed, magazine columns questioned things like “who are the Moonrace?”, “what is the mobile suit that emerges from the stone statue?”, “what does Turn A even mean?” People began to connect the dots, i.e. the ∀ mathematical symbol encompassing “all” Gundams. The show would feature original character design by Akira “Akiman” Yasuda of Street Fighter fame, to bridge the gap between anime and video games. Mechanical designs were by Kunio Okawara and Syd Mead, the latter worldwide famous for his neo-futurist contributions to film. And of course, the soundtrack would be composed by Yoko Kanno, who had previously worked with Tomino on Brain Powerd and was coming hot off of Cowboy Bebop. These are big names! So let’s dive into how this cast was assembled.

AKIRA “AKIMAN” YASUDA

As briefly touched on in Part I in the mid-late 90s Tomino began a partnership with Marigul Management, a company seeking to provide a safe haven for creative minds to focus on original game design. This allowed him the opportunity to dabble in video game design, and in one venture he was able to approach Capcom with a proposal. While the talks didn’t amount to much, it was through this encounter that he met Akira “Akiman” Yasuda, who was employed with Capcom at the time. For Akiman this was a dream come true; he was part of the “Gundam Generation” who grew up with shows like Mobile Suit Gundam. He enjoyed its sense of “reality”, and he projected himself onto Amuro and related to his emotional ups-and-downs and rivalry with Char. He also fell in love with mobile suits such as the RX-78-2, the Zeta Gundam, and even the Walker Gallia from Xabungle. He was inspired by Yoshikazu Yasuhiko’s art style and sought to become an animator like him, however he never made the cut and instead entered the video game industry. Akiman has an incredibly high opinion of Tomino: he viewed him as a “god”, a “professional amongst professionals”, a person with unparalleled influence and incredible track record—yet humble enough to never acknowledge himself as a genius, a mysterious being who has very high standards yet denies his own work. He also related to his ongoing battle with depression and felt he had to do something to alleviate his pain.

So Akiman was, to say the least, excited to exchange autographs with his hero. Tomino gave him a signed booth photo, and Akiman drew a quick sketch of Chun-Li from Street Fighter in return. Tomino was awestruck at his passionate way of drawing—the movement of his elbow, his pen strokes, the way he used his hands to support the paper, and the sparkle in his eyes. For Tomino, it was love at first sight. He knew Akiman had to be the character designer for his new project. They met again a month later and Tomino asked if he’d like to do character design for Gundam. Tomino was, perhaps unsurprisingly, struck by Chun-Li and wanted to have Gundam characters with a similar design aesthetic. Akiman was elated, and what should have been an impossible alliance actually ended up working smoothly, as Capcom executives were accommodating and allowed him to join the project on a contractual basis. It’s worth noting that Tomino had choice words for Street Fighter II and fighting games in general—they’re definitely not his cup of tea. The earliest character concept drawings were completed in June of 1997, before preliminary character roles or setting details had really been established. Some of these designs remained well into “Ring of Gundam”, while others were changed.

In the year leading up to Turn A Gundam, Akiman practiced different styles to prepare for the project. Knowing that it was a Gundam show, he felt great pressure and responsibility. He officially moved to Sunrise Studio 1 in October of 1998 to work full-time with the staff, just as Brain Powerd was in its final stretch of production. He was immediately nervous because of how frankly producers and other staff members spoke to Tomino—Yoshiyuki Tomino, the “God” of anime himself! Most of the studio staff were supportive of him, and he got along particularly well with Atsushi Shigeta (animator and mecha designer), Tsukasa Dokite (animator), and Yoshihito Hishinuma (animation director). Tomino was impressed by his work ethic; Akiman brought his own set of acrylic paints and settled down in a corner of the studio to work on oil paintings. He also wasn’t self-absorbed and listened to and incorporated ideas from Tomino’s proposed compositional layouts. He spent more time sleeping underneath his computer desk in the studio than in the cheap apartment Sunrise provided for him.

As the show’s premise and setting were revised, Akiman had to make many changes to the character designs. He referenced Victorian (1837-1901), Edwardian (1901-1910), and the Belle Époque (1880-1914) eras for inspiration to create his own brand of clothing design. He also watched recordings of the 1996 Takarazuka Revue production of the German-language musical “Elisabeth”. He was basically either designing a new character or making revisions to existing ones on a weekly basis, a challenge he willingly stepped up to face. For instance—as mentioned in Part II—Tomino’s exposure to the Takarazuka Revue caused Loran’s design to undergo significant changes. The character he struggled with the most was Kihel Heim and subsequently Dianna Soreil, mainly because he did not particularly like blonde characters. Tomino wanted Loran to be in love with someone like “Kihel” versus a childhood friend type, so Akiman used Reika Ryuuzaki from Aim for the Ace! as a model to create his own ideal upper-class blonde beauty and referenced Koros from Daitarn 3 and Physis from Toward the Terra for “Dianna”. One of Akiman’s early major tasks was to draw a TV promotional poster based on Tomino’s composition. It was a difficult assignment that took over a month of nonstop work, and a lot of additional pressure was placed on him since Tomino intended to show the poster to Rieko Takahashi (Dianna-Kihel’s VA). Of course, she ended up loving it. Moving forward, Akiman changed his mindset. He began asking staff members to serve as models, he attended scenario meetings to gain a better understanding of the story and visualize its setting, and he also started viewing in-studio discussions as a “drama” of its own. These changes in mindset allowed him to flourish. Before the show aired, he briefly returned to Capcom to much applause from his bosses and coworkers, and when the show began to air he had to work at a much faster pace.

During Brain Powerd Tomino had hoped to pioneer with Mutsumi Inomata as character designer, an animator and manga artist who’d gain worldwide recognition with the Tales of JRPG series. With Turn A Gundam he hoped to do the same in Akiman, a top talent in the video game industry, and bridge the gap between anime and gaming to breathe new life into the anime industry. He viewed Akiman’s designs as animatic and “symbolically real”, and he also valued his freedom and laid-back nature. He felt the contrast between Akiman’s character designs and Syd Mead’s mecha designs would aesthetically balance each other out. Unfortunately, Akiman might have been ahead of his time, as his designs did not particular boost Turn A Gundam‘s popularity when it aired. In the modern day however, his character designs and illustrations are often viewed as a pillar that has boosted the show’s sense of individuality. In the years to follow, Akiman would become a freelancer and continue working with Tomino on anime projects, such as King Gainer (2002) and Gundam Reconguista in G (2014) & its films (2019-2022).

SYD MEAD

Syd Mead was an industrial designer and visual futurist internationally recognized for his contributions to science-fiction films such as Blade Runner, Aliens, and Tron. Tomino’s introduction to Mead was his Land Yacht design from the June 1975 issue of Playboy magazine, and he quickly fell in love with his work. In 1984, Sunrise approached Mead to request designs for the canned Lion’s Gate Gundam live-action film project. They also commissioned him to draw a promotional poster for Zeta Gundam featuring the Gundam Mk-II. This is when Tomino and Mead met for the first time, and they quickly became acquainted.

In June of 1998 Tomino approached Mead about working on Turn A Gundam as its lead mechanical designer, and a month later he was flown out to Japan. Mieko Ishikawa was Mead’s manager at the time, and she served as a liaison between both parties in terms of translation & interpretation and business negotiations. Mead met with Tomino, his wife, and their daughter at a private restaurant, where Tomino gave him a brief overview of the project and his goals. He later met with Sunrise staff and executives to bounce ideas and negotiate; Tomino wanted him to treat the scale of the project on the level of a Hollywood production. Within hours, the staff came together to move forward with Mead’s involvement. He looked back at this moment fondly, as he found it thrilling when a team of talented individuals come to a consensus in order to create something worthwhile.

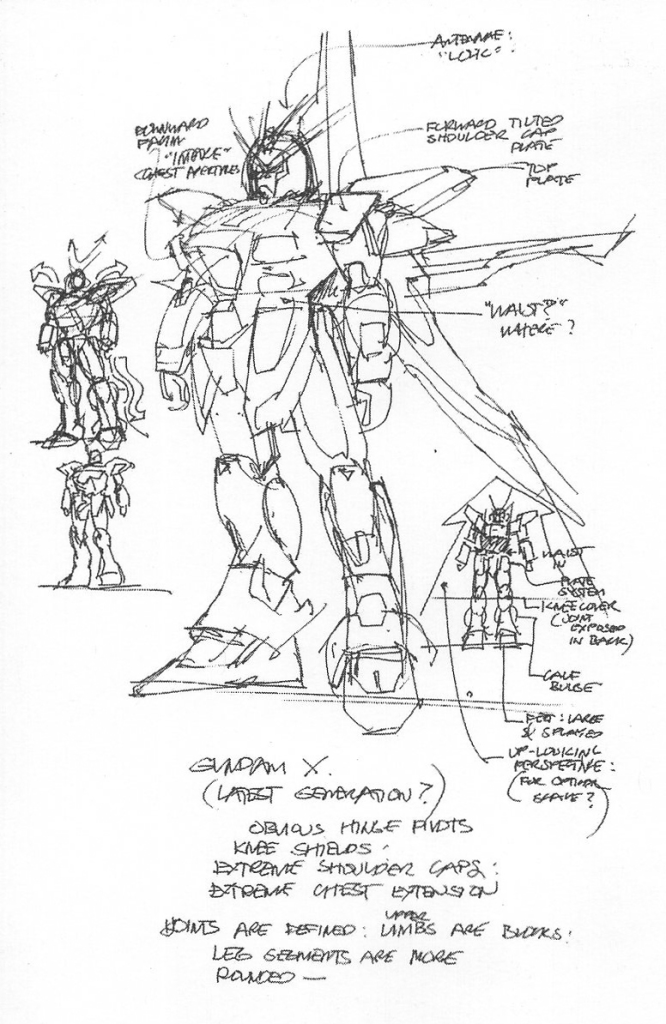

Mead was hired on to essentially develop a new “zero-base” for Gundam design that would simultaneously be recognizable to fans. He considered it a difficult task, since it was a series with twenty years of fan memory, so he had to be cautious when adding onto existing design expectations. Sunrise sent him concept plans, ideas, and sketches of mobile suits, as well as a catalog of previous titular Gundam designs for reference purposes (he was particularly fond of the Wing Zero from Endless Waltz). Mead studied Kunio Okawara’s Gundam design career in detail and referenced his work countless times when designing his own mobile suits. He had a lot of respect for Okawara’s legacy, his attention to detail and shapes & forms, and his focus on mechanical joint structure and block-like arm philosophy. He credited Okawara heavily for his own success.

For the majority of the project, Tomino and Mead communicated via faxes handled by their representatives—Sunrise’s liaison Shigeru Horiguchi and Mead’s manager Mieko Ichikawa. Tomino would provide notes and comments and approve or disapprove of design changes and philosophies. He valued Mead’s professionalism and ability to meet all the deadlines amidst a busy schedule. He had heard from behind the scenes that Mead struggled with many of the designs and was unpleasant to work with. Yet whenever Shigeru Horiguchi received drafts from him, Mead would be quite the gentleman and ask him out for drinks. He acted smoothly as if he had completed his tasks with ease, a manner-of-acting Tomino referred to as “American dandyism”. The titular Turn A Gundam’s design process consisted of two phases. The first phase explored two design paths to finalize on an overall design, and in the second phase all the engineering specifics were detailed. Mead’s early concept presentations were called the “O” and “M” series, larger bulkier machines akin to a sumo wrestler that had little resemblance to the final design. Mead thought that the Turn A Gundam should be bulky because it was a machine used by kids & young adults, his practical designer sense kicking in. Both designs were rejected, but the latter “M” series was later repurposed into the SUMO. Tomino requested that the design be “sleek” and “graceful”, like a kick-boxer instead of a sumo wrestler, and that the face needed to be more distinct and inside its helmet, like a “persona”. He also requested the cockpit to be in the “womb position”, not unlike the Brains from Brain Powerd, and while Mead found this “uterus”-focus to be odd he didn’t question the mindset. There was also emphasis placed on simplifying the design as much as possible to make it easier for animators to draw. The “M” series concept design was then modified and matured to finalize the base design of the Turn A Gundam as we know it. Following this, the design process entered its second phase. All the finer details were explored—cockpit design, upper body & waist, arm & shoulder, legs, weapons systems, etc. This followed Mead’s “inside-out” design philosophy, which consisted of detailing all the individual components & mechanisms to fit an outer framework, with special attention given to joints, rotational axes, and torsion mechanics. This manifests itself into the show very well too, with plenty of scenes involving the Turn A Gundam’s head, its arms or its hands being rotated or twisted in interesting ways.

Once the titular Gundam’s design was finalized, Mead moved onto the SUMO, the FLAT, the WaDom, and other smaller machines. When later portions of the plot were being explored, he was tasked to design the Bandit and Turn X—the latter proved to be Mead’s most challenging design. He flew to Tokyo to meet with studio staff, where Tomino requested a mobile suit to rival the Turn A. He drew 100 sketches in 10 days, with abstract concepts such as an “immortal warrior” and “terrifying bad dream” used to guide his design philosophy. Much like the Turn A, its design process consisted of two phases; one to formalize the overall mechanical design, then followed by finer detailing of the legs & waist, thorax structure, separation module, backpack, and weaponry. After completing most of the design, Mead and his team traveled to Izu to celebrate where he was struck by the mountainside of pink cherry blossoms. In a final moment of inspiration he drew out the Turn X’s final details.

Syd Mead’s designs faced scrutiny by rabid fans and the media alike. Before the show even aired, the titular Gundam was being referred to as the “Mustache Gundam” and Mead’s face became a target of hatred for “ruining” the Gundam brand. This negative sentiment and growing reputation ate away at Tomino, who himself was still battling depression. It’s worth noting that the Turn A Gundam’s mustache was not even intended to be a “mustache”, per se, but rather a steady lowering of the iconic V-fin. The “mustache” connotation was so prominent that it even found its way into the show, conveniently befitting of the “two in one and one in two” thematic duality. Mead ultimately believed that fan opinion of the Turn A would warm up over time—and he was right! For instance, the Turn A Gundam was selected by fan poll in 2007 to have the honor of being the 100th release of the Master Grade line of Gundam model kits. Mead’s experience working on Turn A Gundam was positive, and he had nothing but great things to say about the many Sunrise staff members who facilitated the partnership and allowed him to succeed in his work. He enjoyed seeing his designs come to life in context of a story, and he’s glad Tomino created a story with a retro time period and ecotechnology.

Syd Mead passed away on December 30, 2019 and left behind a mark and legacy that shall be remembered. For additional reading I recommend his interview on the Turn A Gundam DVDs, along with Mead Gundam.

YOKO KANNO

Yoko Kanno and Yoshiyuki Tomino first met during Victory Gundam (1993) where Kanno played a minor role as a pianist on its soundtrack (she’s credited on the second CD “Score II”), which was her proper introduction to the franchise. The two would collaborate again on Brain Powerd (1998) and Turn A Gundam (1999), this time as primary composer. Her role in Turn A Gundam had already been decided before she was invited to work on Brain Powerd. It was a natural move as both shows aimed to have many women on staff, hence a lot of carryover between the two, notably in scriptwriting and voice acting. During Brain Powerd, Kanno struggled to decipher Tomino’s unique way of expressing himself. She found his plot outlines incomprehensible and his music direction sparse and unclear. She had to continuously ask for clarification on his notes, and this created a bit of a disconnect in her music compositions. Nevertheless, Brain Powerd‘s music is highly-acclaimed and Kanno herself describes it as “mysterious” and “heart-pounding”. By Turn A Gundam, she had learned the way Tomino operates and her creative freedom and prowess exploded. In recording its soundtrack, Kanno sought to make it feel “real”, akin to a live concert, so she didn’t go out of her way to remove tiny mistakes. She valued the authenticity in including the odd instrumental note here and there. She wanted to compose a soundtrack that could convey the melancholic history of Gundam and its fascination with giant robots. Her thoughts culminated in tracks like “Moon”, which Kanno herself sings under the Gabriela Robin pseudonym.

Tomino has an incredibly high opinion of Yoko Kanno, calling her a genius and prodigy who’s easy to work with. He respects her passion for music and likes how she has high standards and is difficult to impress. He also thinks she provides a unique perspective as a woman and perceives art in a way older men like him can’t grasp. During their time on Brain Powerd and Turn A Gundam, he felt he learned a lot from her. Kanno enjoyed Tomino’s company because he reminds her of her father, both in age and temperament, only it’s less awkward to actually talk to him about the arts. They had many deep and intellectual conversations, and she valued the opportunity to get his insight on raising daughters.

She would go on to enjoy Turn A Gundam and follow it weekly as it aired. She loved the show’s aesthetic and its sense of character movement, in how the characters strut around in fluttering dresses. She liked most of its character cast but was particularly drawn to Harry Ord (whom she calls “Harry-sama”), Lily Borjarno, and Guin Lineford. Kanno always felt that Turn A Gundam had a surface-level aesthetic sense of a “love story”, since it’s a drama where the fate of the characters are intertwined and it doesn’t have as much of a focus on giant robots as previous Gundam titles.

For additional reading, I recommend my breakdown of the Turn A Gundam concert.

Tomino wanted to draw on the widespread success of Takarazuka stage performances and Ghibli films, so Turn A Gundam was meant to reach a wide-ranging audience (ages 10-37) and appeal to both kids and adults, men and women. With the ∀ symbol (“for all”), he wanted to showcase humanity’s revolving nature and how one can simultaneously accept & deny their past when moving forward. He also pushed for the show to have a healing effect, to convey a sensation of acceptance and happiness.

The ultimate goal was to overcome the “barrier” that is Gundam. It is why he sought a team not “tainted” by Gundam-like ideas which had plagued the franchise, and it is why he consulted with people like Hiroyuki Hoshiyama and incorporated talents from outside the industry. He also slowly began to place trust and faith in his supporting staff, like in his headbutting encounter with “Turn A Turn” singer Hideki Saijo, and this is ultimately what allowed Turn A Gundam to flourish as a studio work, particular with the younger staff. Tomino felt that Gundam had to evolve because since it’s conception it had no real competition as a “hard”/real-robot anime, and it needed to move past simply being a promotional program for toy companies. Early concept drafts of Turn A Gundam included Newtypes as a concept but it was quickly removed, because Tomino came to the conclusion that humanity could not actually achieve the peace that “Newtypism” promoted. He viewed it as a failed ideology and amateur-like philosophy he had had in the past. He has compared “Newtypism” to organized religions like Christianity in how their doctrines and standards took hundreds or thousands of years to modernize, and he does not believe religions can be unified in today’s world due to intolerance. He only accepted animism, which went hand-in-hand with the show’s idyllic atmosphere. Tomino has compared the hurdles he faced in creating Turn A Gundam to that of the original Mobile Suit Gundam. Like MSG, he wanted to create something new and atypical but faced backlash from staff and producers. For instance, as previously discussed, he got into heated arguments with a few staff members who inevitably resigned in protest over Guin Lineford’s homosexuality. It also took a lot of effort to get the producers on-board with the idea of the Dark History. MSG was initially ridiculed and had low TV ratings, and people didn’t like that the robots were called “mobile suits” and thought Char’s dialogue was silly. Turn A Gundam faced a similar parallel in Syd Mead’s designs with the titular Gundam being ridiculed as the “Mustache Gundam”—all before the show even aired—and it also had low TV ratings.

Turn A Gundam‘s first episode was screened in advance to staff members and industry people, and it was officially broadcast on Fuji TV on April 9, 1999. Many challenges still remained to overcome, but Tomino’s return to Gundam had officially begun. The next and final part of this blog post series will examine in detail the production era as Turn A Gundam aired.

These articles were made possible by various supplementary materials, my friends & family, and personal staff/industry contacts who graciously allow me to pester them for information. For a complete breakdown on my sources, please check out the associated page. This is all a culmination of my continued research into my favorite anime. Thank you.

Reading how Tomino removed any mention of newtypism from Turn A as he felt it was a failed philosophy that could never work gets me thinking… Was the light-novel turned OVA Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn made as a deliberate response to his current beliefs?

I mean think about it: Both continue prior works in the series (Turn A subtly, Unicorn openly), both feature overpowered lead suits (The titular Turn A and Unicorn), and both almost seem to be made to be at odds with one another: one is a full TV show that tells us that religion, race and beliefs must be cast aside for animism if we are to live in a better future, whilst the other is an 6 hour-long episode OVA with a double-length finale that very much so, from the third episode onwards tells us YES, man CAN evolve into a higher being and gain better understanding of eachother, even if it will take a long time to get there. I’d honestly doubt it, but as someone going through Unicorn, it deserves mentioning.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know much about the history behind Gundam Unicorn, but I doubt it was specifically made in response to counter said beliefs/mentality. Fukui is a massive Tomino fan and even penned one of the Turn A Gundam novelizations.

LikeLike

Oh, okay. Unicorn does play out partially as a loveletter to the old UC shows Tomino wrote, so I’m not surprised he’s a fan of those shows and Turn A. All the more reason to check out Turn A one of these days. Seriously though, the parallels between Turn A Gundam and Mobile Suit Gundam Unicorn. WTF.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder why Tomino on this book didn’t mention that he was also directing Garzey’s Wing around this period. I remember when ANN tried (more like harassed him) to ask Tomino with a barrage of questions about GW and Tomino preferred not to talk about it.

LikeLike

If by book you mean “Turn A no iyashi”, then he does mention it a few times in there. I can’t speak for Garzey’s Wing entirely, but I do know he wasn’t in the best mental space when writing it.

LikeLike

I just wanted you to know that this is one of the most amazing blogs I’ve ever read.

LikeLiked by 1 person